04 Dec 2015 by Fabian Hueske (@fhueske)

The data analysis space is witnessing an evolution from batch to stream processing for many use cases. Although batch can be handled as a special case of stream processing, analyzing never-ending streaming data often requires a shift in the mindset and comes with its own terminology (for example, “windowing” and “at-least-once”/”exactly-once” processing). This shift and the new terminology can be quite confusing for people being new to the space of stream processing. Apache Flink is a production-ready stream processor with an easy-to-use yet very expressive API to define advanced stream analysis programs. Flink’s API features very flexible window definitions on data streams which let it stand out among other open source stream processors.

In this blog post, we discuss the concept of windows for stream processing, present Flink’s built-in windows, and explain its support for custom windowing semantics.

What are windows and what are they good for?

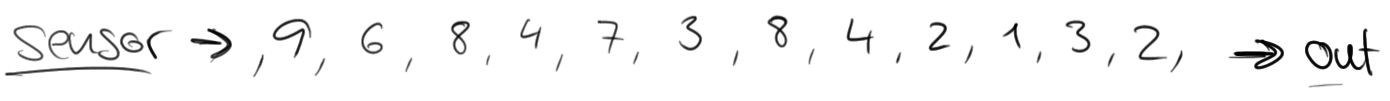

Consider the example of a traffic sensor that counts every 15 seconds the number of vehicles passing a certain location. The resulting stream could look like:

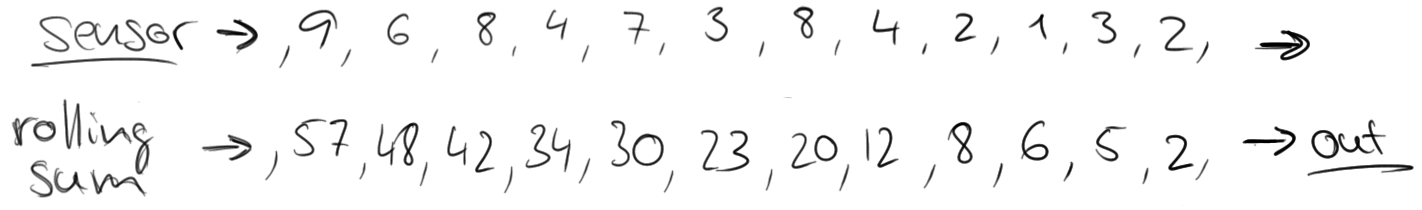

If you would like to know, how many vehicles passed that location, you would simply sum the individual counts. However, the nature of a sensor stream is that it continuously produces data. Such a stream never ends and it is not possible to compute a final sum that can be returned. Instead, it is possible to compute rolling sums, i.e., return for each input event an updated sum record. This would yield a new stream of partial sums.

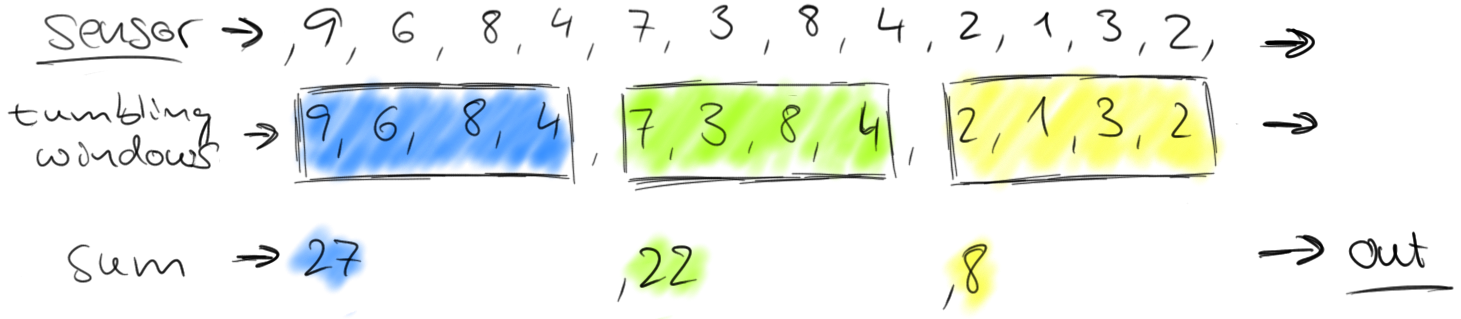

However, a stream of partial sums might not be what we are looking for, because it constantly updates the count and even more important, some information such as variation over time is lost. Hence, we might want to rephrase our question and ask for the number of cars that pass the location every minute. This requires us to group the elements of the stream into finite sets, each set corresponding to sixty seconds. This operation is called a tumbling windows operation.

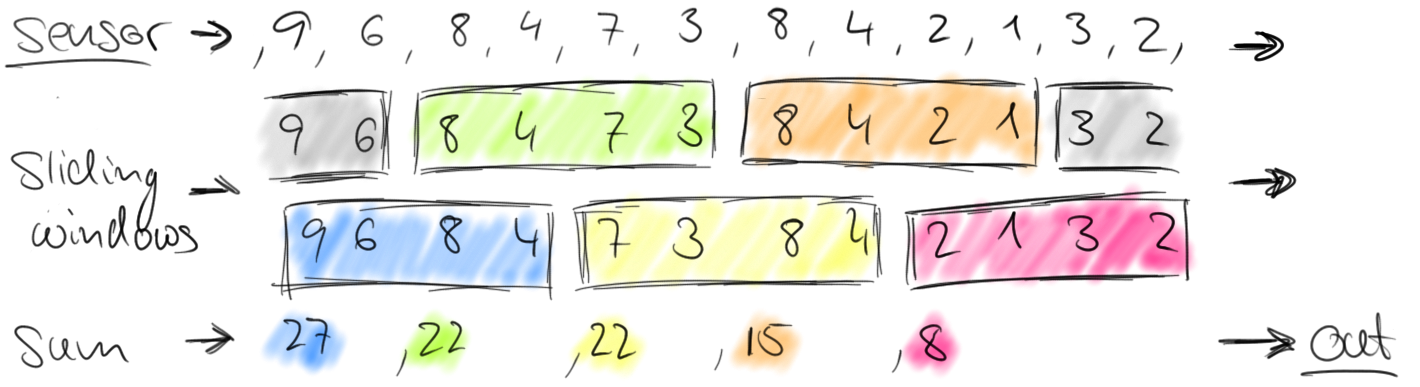

Tumbling windows discretize a stream into non-overlapping windows. For certain applications it is important that windows are not disjunct because an application might require smoothed aggregates. For example, we can compute every thirty seconds the number of cars passed in the last minute. Such windows are called sliding windows.

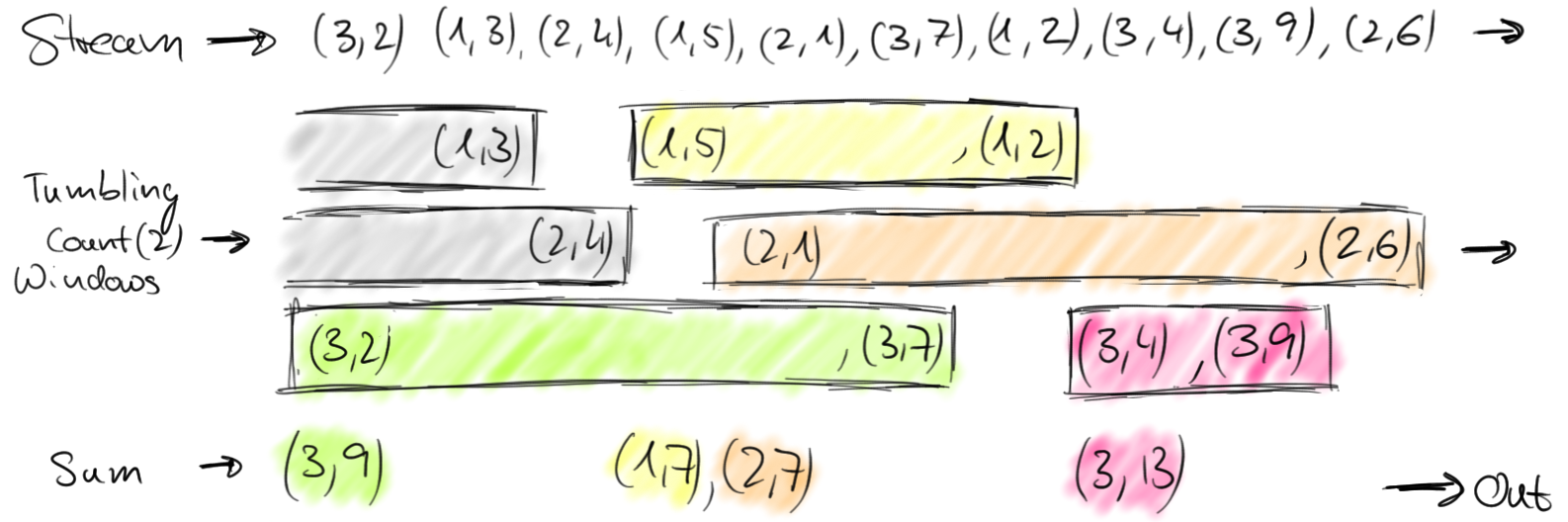

Defining windows on a data stream as discussed before is a non-parallel operation. This is because each element of a stream must be processed by the same window operator that decides which windows the element should be added to. Windows on a full stream are called AllWindows in Flink. For many applications, a data stream needs to be grouped into multiple logical streams on each of which a window operator can be applied. Think for example about a stream of vehicle counts from multiple traffic sensors (instead of only one sensor as in our previous example), where each sensor monitors a different location. By grouping the stream by sensor id, we can compute windowed traffic statistics for each location in parallel. In Flink, we call such partitioned windows simply Windows, as they are the common case for distributed streams. The following figure shows tumbling windows that collect two elements over a stream of (sensorId, count) pair elements.

Generally speaking, a window defines a finite set of elements on an unbounded stream. This set can be based on time (as in our previous examples), element counts, a combination of counts and time, or some custom logic to assign elements to windows. Flink’s DataStream API provides concise operators for the most common window operations as well as a generic windowing mechanism that allows users to define very custom windowing logic. In the following we present Flink’s time and count windows before discussing its windowing mechanism in detail.

Time Windows

As their name suggests, time windows group stream elements by time. For example, a tumbling time window of one minute collects elements for one minute and applies a function on all elements in the window after one minute passed.

Defining tumbling and sliding time windows in Apache Flink is very easy:

// Stream of (sensorId, carCnt)

val vehicleCnts: DataStream[(Int, Int)] = ...

val tumblingCnts: DataStream[(Int, Int)] = vehicleCnts

// key stream by sensorId

.keyBy(0)

// tumbling time window of 1 minute length

.timeWindow(Time.minutes(1))

// compute sum over carCnt

.sum(1)

val slidingCnts: DataStream[(Int, Int)] = vehicleCnts

.keyBy(0)

// sliding time window of 1 minute length and 30 secs trigger interval

.timeWindow(Time.minutes(1), Time.seconds(30))

.sum(1)There is one aspect that we haven’t discussed yet, namely the exact meaning of “collects elements for one minute” which boils down to the question, “How does the stream processor interpret time?”.

Apache Flink features three different notions of time, namely processing time, event time, and ingestion time.

- In processing time, windows are defined with respect to the wall clock of the machine that builds and processes a window, i.e., a one minute processing time window collects elements for exactly one minute.

- In event time, windows are defined with respect to timestamps that are attached to each event record. This is common for many types of events, such as log entries, sensor data, etc, where the timestamp usually represents the time at which the event occurred. Event time has several benefits over processing time. First of all, it decouples the program semantics from the actual serving speed of the source and the processing performance of system. Hence you can process historic data, which is served at maximum speed, and continuously produced data with the same program. It also prevents semantically incorrect results in case of backpressure or delays due to failure recovery. Second, event time windows compute correct results, even if events arrive out-of-order of their timestamp which is common if a data stream gathers events from distributed sources.

- Ingestion time is a hybrid of processing and event time. It assigns wall clock timestamps to records as soon as they arrive in the system (at the source) and continues processing with event time semantics based on the attached timestamps.

Count Windows

Apache Flink also features count windows. A tumbling count window of 100 will collect 100 events in a window and evaluate the window when the 100th element has been added.

In Flink’s DataStream API, tumbling and sliding count windows are defined as follows:

// Stream of (sensorId, carCnt)

val vehicleCnts: DataStream[(Int, Int)] = ...

val tumblingCnts: DataStream[(Int, Int)] = vehicleCnts

// key stream by sensorId

.keyBy(0)

// tumbling count window of 100 elements size

.countWindow(100)

// compute the carCnt sum

.sum(1)

val slidingCnts: DataStream[(Int, Int)] = vehicleCnts

.keyBy(0)

// sliding count window of 100 elements size and 10 elements trigger interval

.countWindow(100, 10)

.sum(1)Dissecting Flink’s windowing mechanics

Flink’s built-in time and count windows cover a wide range of common window use cases. However, there are of course applications that require custom windowing logic that cannot be addressed by Flink’s built-in windows. In order to support also applications that need very specific windowing semantics, the DataStream API exposes interfaces for the internals of its windowing mechanics. These interfaces give very fine-grained control about the way that windows are built and evaluated.

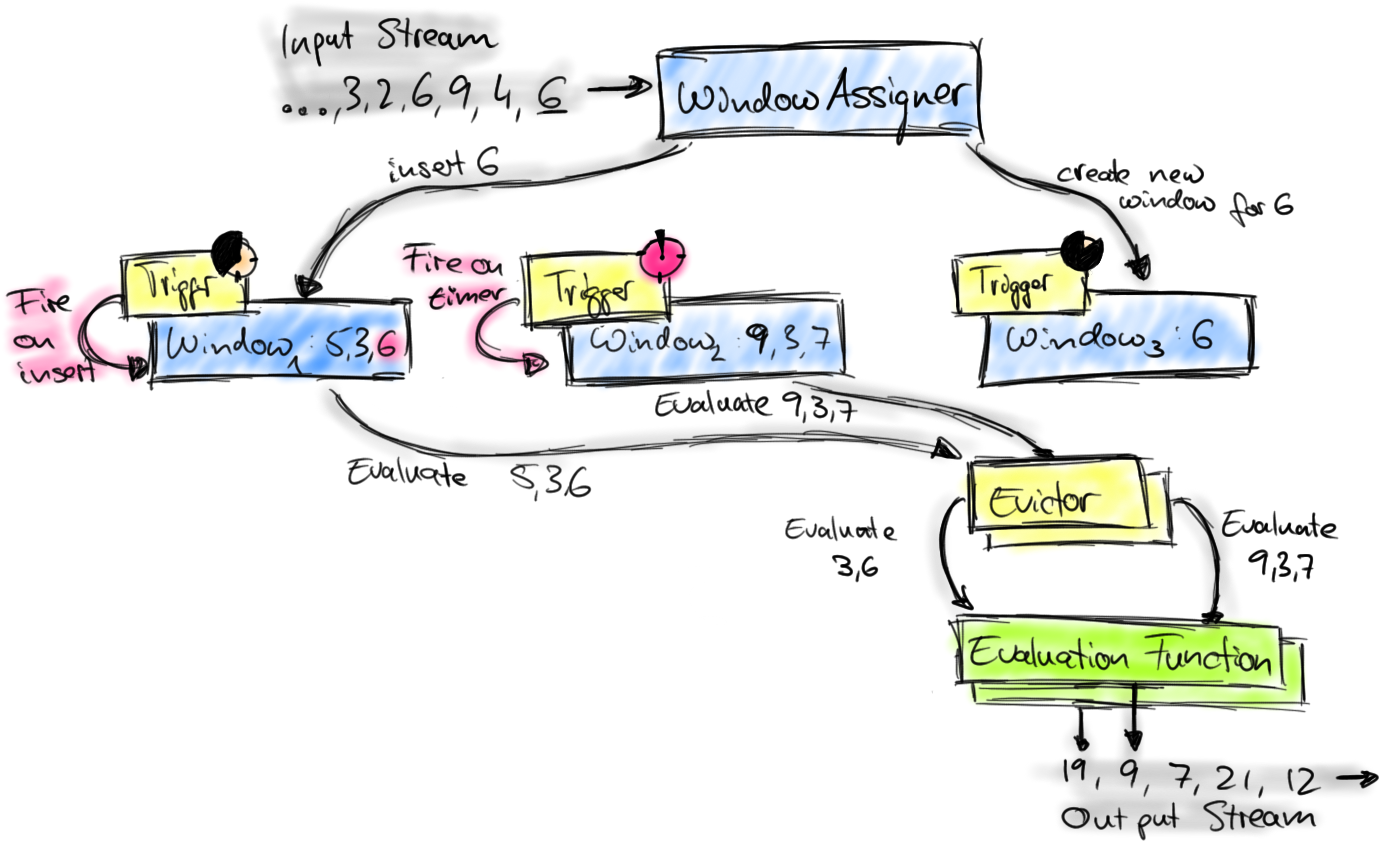

The following figure depicts Flink’s windowing mechanism and introduces the components being involved.

Elements that arrive at a window operator are handed to a WindowAssigner. The WindowAssigner assigns elements to one or more windows, possibly creating new windows. A Window itself is just an identifier for a list of elements and may provide some optional meta information, such as begin and end time in case of a TimeWindow. Note that an element can be added to multiple windows, which also means that multiple windows can exist at the same time.

Each window owns a Trigger that decides when the window is evaluated or purged. The trigger is called for each element that is inserted into the window and when a previously registered timer times out. On each event, a trigger can decide to fire (i.e., evaluate), purge (remove the window and discard its content), or fire and then purge the window. A trigger that just fires evaluates the window and keeps it as it is, i.e., all elements remain in the window and are evaluated again when the triggers fires the next time. A window can be evaluated several times and exists until it is purged. Note that a window consumes memory until it is purged.

When a Trigger fires, the list of window elements can be given to an optional Evictor. The evictor can iterate through the list and decide to cut off some elements from the start of the list, i.e., remove some of the elements that entered the window first. The remaining elements are given to an evaluation function. If no Evictor was defined, the Trigger hands all the window elements directly to the evaluation function.

The evaluation function receives the elements of a window (possibly filtered by an Evictor) and computes one or more result elements for the window. The DataStream API accepts different types of evaluation functions, including predefined aggregation functions such as sum(), min(), max(), as well as a ReduceFunction, FoldFunction, or WindowFunction. A WindowFunction is the most generic evaluation function and receives the window object (i.e, the meta data of the window), the list of window elements, and the window key (in case of a keyed window) as parameters.

These are the components that constitute Flink’s windowing mechanics. We now show step-by-step how to implement custom windowing logic with the DataStream API. We start with a stream of type DataStream[IN] and key it using a key selector function that extracts a key of type KEY to obtain a KeyedStream[IN, KEY].

val input: DataStream[IN] = ...

// created a keyed stream using a key selector function

val keyed: KeyedStream[IN, KEY] = input

.keyBy(myKeySel: (IN) => KEY)We apply a WindowAssigner[IN, WINDOW] that creates windows of type WINDOW resulting in a WindowedStream[IN, KEY, WINDOW]. In addition, a WindowAssigner also provides a default Trigger implementation.

// create windowed stream using a WindowAssigner

var windowed: WindowedStream[IN, KEY, WINDOW] = keyed

.window(myAssigner: WindowAssigner[IN, WINDOW])We can explicitly specify a Trigger to overwrite the default Trigger provided by the WindowAssigner. Note that specifying a triggers does not add an additional trigger condition but replaces the current trigger.

// override the default trigger of the WindowAssigner

windowed = windowed

.trigger(myTrigger: Trigger[IN, WINDOW])We may want to specify an optional Evictor as follows.

// specify an optional evictor

windowed = windowed

.evictor(myEvictor: Evictor[IN, WINDOW])Finally, we apply a WindowFunction that returns elements of type OUT to obtain a DataStream[OUT].

// apply window function to windowed stream

val output: DataStream[OUT] = windowed

.apply(myWinFunc: WindowFunction[IN, OUT, KEY, WINDOW])With Flink’s internal windowing mechanics and its exposure through the DataStream API it is possible to implement very custom windowing logic such as session windows or windows that emit early results if the values exceed a certain threshold.

Conclusion

Support for various types of windows over continuous data streams is a must-have for modern stream processors. Apache Flink is a stream processor with a very strong feature set, including a very flexible mechanism to build and evaluate windows over continuous data streams. Flink provides pre-defined window operators for common uses cases as well as a toolbox that allows to define very custom windowing logic. The Flink community will add more pre-defined window operators as we learn the requirements from our users.